Beta Transus: Managing Adiabatic Heating During α+β Titanium Forging

As forging engineers, we spend half our time coming up with cool processes and the other half explaining how we promise it will make good parts! One of the biggest forge process risk area in aerospace, medical, and automotive forgings is the Beta Transus Temperature of α+β Titanium alloys.

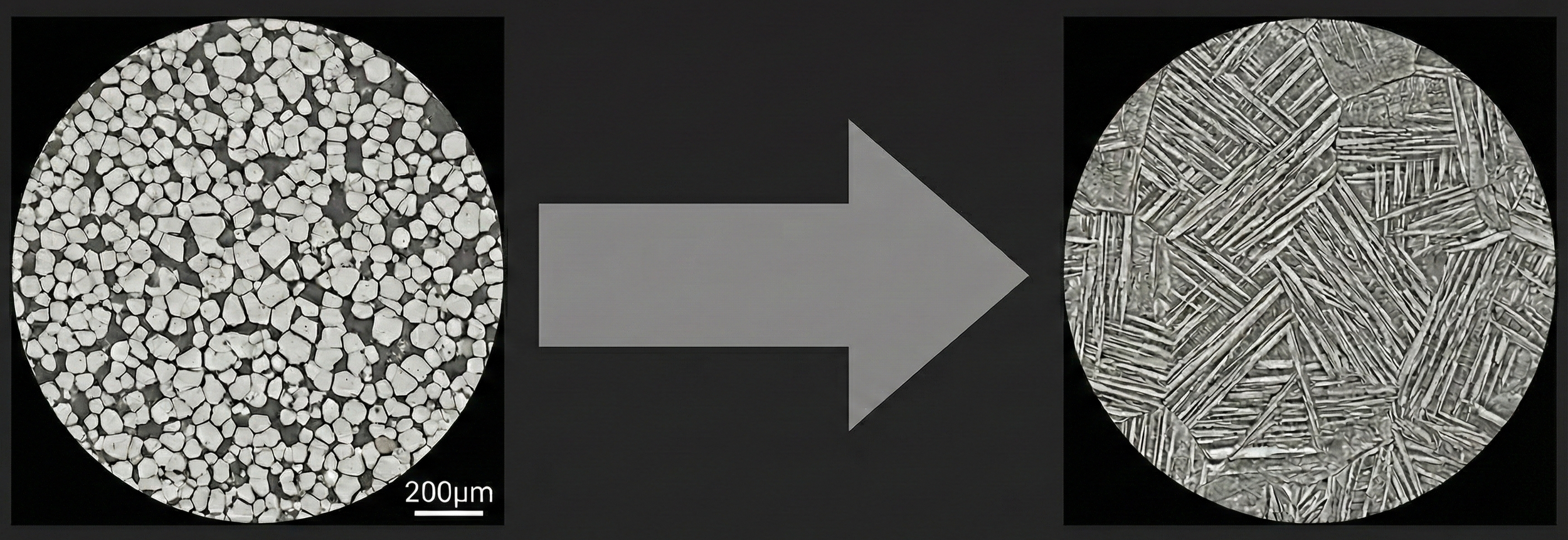

Beta Transus Temperature - the temperature at which titanium alloys completely transform from a two-phase alpha+beta (α+β) microstructure to a single-phase beta (β) microstructure upon heating.

We want to maximize die life and minimize flow stress, while proving we'll stay below the beta transus to meet metallurgical and mechanical specifications.

The challenge is that heat doesn't just come from the furnace. It comes from the process itself. This is Adiabatic Heating, and in Titanium alloys like Ti-6Al-4V, it is the invisible variable that separates a ductile forging from scrap metal.

1. Fundamentals of Titanium Metallurgy

To understand the forging risk, we must first understand titanium’s unique structure. Titanium is “allotropic”, meaning it can exist in 2 different atomic arrangements depending on temperature.

Structure & Stability

Pure titanium exists as a Hexagonal Close Packed (HCP) structure, known as the α-phase, at room temperature. This phase is stable up to approximately 882°C (1620°F). Above this temperature, the atoms rearrange into a Body Centered Cubic (BCC) structure, known as the β-phase, which remains stable up to the melting point.

Mechanical Properties & Slip Systems

α-phase (HCP): At room temperature, the hexagonal structure has a limited number of "slip systems" (planes along which atoms can slide). This makes the material stronger and more resistant to creep, but it also results in poorer ductility and difficult formability when cold.

β-phase (BCC): The cubic structure possesses a significantly higher number of active slip planes. This makes the β-phase much more ductile and formable. This is why we heat Titanium to forge it—to access these slip systems and lower the flow stress.

The Alpha-Beta Advantage

Alloys like Ti-6Al-4V (Aerospace) and Ti-6Al-7Nb (Medical) use Aluminum to stabilize the Alpha phase and Vanadium/Niobium to stabilize the Beta phase. Forging in the mixed "Alpha-Beta Field" gives us the workability of Beta while retaining the strength of Alpha.